Exploring TypeScript: Primitive Types

A deep dive into 7 primitives

This is part of a semi-monthly series that will put TypeScript under a microscope to become more adept overall. 🔬

Understanding the nitty gritty bits and pieces of a language can only benefit us as software builders!

This post will cover basic primitive types within TypeScript.

🤔 What are primitive types?

📚 Resources for further reading

Let's dive in!

You’re probably thinking, “Why are we going so low-level and foundational?”

Now that we’ve covered the TypeScript Compiler and Runtime, primitive types are a natural next step in continuing to build upon a strong foundation. The stronger the base knowledge, the better we can grow toward more advanced topics.

So, let’s take it from the top!

🤔 What are primitive types?

To start, we need a shared understanding of the types we will discuss. Because TypeScript is a superset of JavaScript, these types will naturally mirror some JavaScript.

A few differences exist between JavaScript primitives and TypeScript primitives, mainly relating to the types themselves because TS is a superset of JS. The TypeScript documentation is your best source if you have questions about TypeScript primitives!

What is a “primitive” in the sense of programming?

Consider a primitive as a very low-level and built-in aspect of a language. It describes the specific data type of one specific value. They are also what the built-in typeof operator might return in some cases.

These types are immutable. They can be assigned to a variable, and a variable can have its value reassigned, but that does not change the type of the initial value itself.

In JavaScript, a primitive (primitive value, primitive data type) is data that is not an object and has no methods or properties.

Let’s take a look at the primitives that span across both JavaScript and TypeScript:

string

number

boolean

bigint

symbol

null and undefined

As a note, you may notice that these types are referred to in lowercase (string, number, boolean). If you see them referred to in uppercase (String, Number, Boolean), these refer to the built-in types that contain the methods and properties of the built-in objects for these types. You can learn more from MDN!

🧵 string

The string type is one of the three most common primitives. It represents data in the form of text. In TypeScript, you can declare the string type using the string keyword, as you might expect:

let name: string = 'Mindi'You’ll notice that single quotes are used in my above example (‘). Double quotes (“) may also be used, as well as backticks (`) for a template literal. These are the same options as in JavaScript, just with the added type declaration. Here are examples using these last two options together:

let dog: string = "Rigby"

const dogCommand: string = `${dog}, please sit."

console.log(dogCommand) // Output: "Rigby, please sit."

dog = "Rayla"

console.log(dogCommand) // Output: "Rayla, please sit."If you weren’t aware, TypeScript is also smart enough to infer types! However, this can come with confusion. In a function, TypeScript would understand that the output will be a string:

const greeting = (str: string) => {

return str

}

console.log (greeting("Hello")) // Output: "Hello"

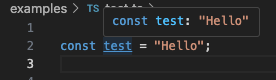

// The type when you hover over `greeting` shows a string typeHowever, if you were to use const variable declaration for a string without declaring it as a string more broadly, TypeScript may infer this as a type literal! Take a look at this example. The variable test is the literal string of “Hello” as its type, not a more generic string!

Why is this? When we use const in this way, we essentially make the variable read-only. The variables are unable to be reassigned and, therefore, remain constant. If we cannot reassign test to, say, “Goodbye” then it makes some sense that its type would be “Hello” as the type literal as opposed to a string.

Although it seems rather simple, I have found nuance is littered throughout TypeScript. Let’s keep this in mind as we examine the remaining primitive types.

When in doubt, hover your mouse in the IDE to check it out! 👀

#️⃣ number

Another of the three most common primitive types is number. As you may have assumed, this type represents number data! These can be integers or floating-point numbers that may or may not contain decimals.

As with the string type, you can declare a variable as a number with the corresponding keyword:

let year: number = 2050

let distance: number = 21.555As with strings, TypeScript will attempt to infer the type if you do not state it:

let age = 100

// hovering over age, shows a type of number

const zero = 0

// hovering over zero shows a type literal of 0As you can see from the variable zero, using const will again cause TypeScript to infer a type literal of 0 as opposed to the more broad number type.

When in doubt, check it out! 👀

⚖️ boolean

The boolean type is the third most common primitive. This refers to the two logical values of true and false.

They are typically used in conditional testing like if…else or while statements that return a truth or false result. You can also use the ternary operator; here’s an example:

let happy = "happy"

let isHappy: boolean = happy === "happy" ? true : false

// hovering over isHappy shows a type of booleanAnd, if you were wondering, a type literal will occur if using const as with the number and string primitives.

const isTrue = true

// hovering over isTrue shows a type literal of trueWhen in doubt, check it out! 👀

🏋 bigint

The bigint primitive is similar to number, but the value is too large to be represented by a typical number.

There are subtle differences between number and bigint. First, the built-in Math objects cannot be used on a bigint value. Additionally, bigint values cannot mix with number values in operations. These number types must be coerced to the same type first. Coercion to a number value, however, can cause degraded bigint precision.

Overall, this primitive is rarely used in my own experience. My work and side projects thus far haven’t dealt with such large numbers! If you have a great real-world example, I’d love to hear more about it. 🤓

For now, here’s a simple example:

let oneBigInteger: bigint = 1nAgain, similar to the previous primitives, using const will result in a type literal:

const aBiggerBigInteger = 100n

// hovering over aBiggerBigInteger shows a type literal of 100nWhen in doubt, check it out! 👀

👾 symbol

Another primitive that I rarely use is a symbol. If you have a great example from your own experience, please share! 🤓

A symbol is an immutable and exclusive value for a property key created using the Symbol() constructor. Strings are optional to provide a key value used to access a symbol at a later time.

This is the only primitive with a reference identity making it unique. In some ways, they behave like objects. Often, a symbol can be used to add a unique property to an object that acts as a hidden mechanism from other code that might typically access a key.

Each symbol creation is completely separate. Let’s take a look:

let example1 = Symbol("example")

let example2 = Symbol("example")

console.log(example1 === example2)

// Output: false, symbols are uniqueIn addition, TypeScript has the concept of a symbol subtype - called unique symbol which allows a symbol to be treated as a unique literal from explicit type annotations.

Similar to the type literals in the above primitives, const can be used to declare a unique symbol or we can use a combination of readonly and static properties. To access or reference the unique symbol, the typeof operator should be used.

Let’s look at an example that my friend GitHub Copilot helped generate using const:

// Define a unique symbol

const uniqueKey: unique symbol = Symbol("uniqueKey")

// Create an interface with a property of type unique symbol

interface MyObject {

[uniqueKey]: string;

}

// Create an object that implements the interface

const obj: MyObject = {

[uniqueKey]: "This is a unique value"

}

// Access the unique property

console.log(obj[uniqueKey]) // Output: This is a unique valueWhen in doubt, check it out! 👀

🍽️ null and undefined

These primitives I use frequently! Both null and undefined express a lack of value, but there are subtle differences. To better explore them, I opted to describe null and undefined together.

Let’s start with null. This means that a variable was defined and null explicitly assigned to express the absence of a value. This value may be intentional or to express that there is no known value yet to apply.

Here’s a quick couple of examples:

// Example 1

let nullExample = null

console.log(nullExample) // Output: null

// Example 2

const nameExample = db.findName()

// We make some call to a database to find a name object.

// No name object was found for the sake of our example!

console.log(nameExample) // Output: null

// If no name was found, we could return a null value

// to make this result clear without throwing an errorMoving on to undefined. This means a variable was declared, but not defined or a value was not assigned. The undefined assignment to the value happens automatically if you do not initialize that variable.

Let’s take a look at a quick example:

let unassignedExample

console.log(unassignedExample) // Output: undefinedWhat are the more subtle differences then?

First, null represents an intentional absence of a value, whereas, undefined typically indicates an unintentional absence of a value. Of course, there are cases to use both intentionally, but null has to be assigned while undefined is automatically assigned when a value is not initiated.

That can be a little confusing, so let’s take a look at an example of undefined where you might use it intentionally. Let’s say we’re trying to apply grade scores to a respective letter grade, but maybe there can be a glitch in the system providing the grade scores.

const numberGrade: number = NaN

// Let's say we got this from an outside source

let letterGrade

if (numberGrade >= 90) {

letterGrade = "A"

} else if (numberGrade >= 80) {

letterGrade = "B"

} else if (numberGrade >= 70) {

letterGrade = "C"

} else if (numberGrade >= 60) {

letterGrade = "D"

} else if (numberGrade >= 0) {

letterGrade = "F"

}

console.log(letterGrade) // Output: undefinedPerhaps we can add some checks for such an undefined incident and handle it appropriately now.

The next difference is that null represents the absence of an object. In our earlier example, we expected a result to be an object containing details about a name record. On the other hand, undefined is a lack of any value at all.

Finally, equality between the two differs. null and undefined are loosely equal (null == undefined), but not strictly equal (null !== undefined). Loose equality performs type coercion and both primitives evaluate to an absence of value. Strict equality, however, checks whether the data types and values are the same and null and undefined are ultimately not the same data types.

When in doubt, always check it out! 👀

I hope that covering these primitives can be at least a little bit informative! In writing this I learned a few new things myself or at least considered aspects of these types I hadn’t before. 🤓

📚 Resources for further reading

O’Reilly Books:

Learning TypeScript by Josh Goldberg

I haven’t read this in full as of this writing, but I’ve seen him speak a few times, and I’m excited to start it after wrapping up a couple of other books!

TypeScript Cookbook by Stefan Baumgartner

I haven’t read it as of this writing, but I’ve heard good things and it’s on my list!

For more stuff from me, find me on LinkedIn / YouTube or catch what else I'm up to at mindi.omg.lol

Thanks for reading! Did I miss anything, or would you like to add anything? Let me know! I appreciate constructive feedback so we can all learn together. 🙌